Mount Radford House, built by John Baring about 1775

Discovering Exeter, 2 St Leonard’s

by Gilbert Venn

First published by

Exeter Civic Society, 1982

Under revision , 2020

Significant changes in red.

Significant changes in red.

Foreword to original edition

This is the second in the Civic Society’s series of booklets, Discovering Exeter. The success of the first one, St David’s, has encouraged the Society to continue the series until all the suburbs of Exeter, as well as the ancient city itself, have been covered. Exeter has a long and distinguished history and, despite much self-inflicted damage, has preserved a great deal of its architectural heritage. Part of the heritage is described and illustrated in this booklet which gives an outline history and descriptive tour both of the residential neighbourhood of St Leonard’s and the working area around the Quay. The Society is greatly indebted to those members who have helped in the preparation of the booklet and especially to Gilbert Venn who has put together a great deal of interesting material in an attractive and readable way. Generous grant-aid from the Iverdean and Northcott Trusts is gratefully acknowledged.

H. J. Trump

Chairman Exeter Civic Society

Historic Introduction

St. Leonard’s was the smallest rural parish in Devonshire until 1877 when, with many protests from its parishioners, it was added to the County of the City of Exeter. But it remained a remote city parish, for its northwest boundary still lay on the course of the Larkbeare Stream as it had done from time immemorial. Between the stream and the city walls lay much of the parish of Holy Trinity which had become urbanised whilst St. Leonard’s remained the domain of “Parson and Squire.” In 1969 Holy Trinity parish was united with St. Leonard’s because of the decline of its residential population; thus ended for Holy Trinity an era rich in historical interest.

At the beginning of the 19th century St. Leonard’s had a total of 26 houses and 133 inhabitants — few more than for centuries past; but by the end of the century, in which the domination of the Squire gave way to the activities of builders, its houses could be counted in hundreds and its inhabitants in thousands. Its growth has continued during the 20th century, and today it is an integral part of our city with a distinct character of its-own.

The Larkbeare Stream lay in a deep wooded ravine in which, woodlarks nested and gave song and their name to Larkbeare (Lark Wood). Rising near Belmont, the stream — known in various times as the Schytebrook (Shitbrook), Sutbrook and later Larkbeare — still flows (deep down in culverts since 1845) below Clifton Street, Barnfield, Bull Meadow and Roberts Road. To join the Exe at the foot of Colleton Hill. Its coarse early name implies that the stream was used as an open sewer, but this did not deter the establishment on its banks of the house of Larkbeare in the 13th century, and it is evident from early maps of the area that the stream was culverted within the precincts of the house and gardens.

Crossing the woodland stream at the foot of what is now Holloway Street, a steep track would have led up to “St. Leonard’s Down” — giving a panoramic view of the city and surrounding countryside from where Barnardo Road now stands. From this vantage point the attackers and defenders of the city’s south flank were engaged at intervals from the coming of the Romans to the end of the Civil Wars in mid-17th century.

From South Gate the Romans laid the courses of three routes in use today: Magdalen Street and Magdalen Road away to the east; Holloway Street and Topsham Road to their outport at Topsham; and Quay Lane, now a footpath following outside the city walL down to the Quay. Roman remains found in St. Leonard’s consist of a coin of the Emperor Galienus, the site of one of their cemeteries in the vicinity of the present West of England Eye Hospital, and a Roman military establishment discovered in 2010, a little outside the historic parish to the north of St Loyes when that area was under redevelopment.

Statue of St Leonard

After the Romans, little is known of Exeter’s life-style until the mid-7th century when the Anglo-Saxons held Wonford as a large royal estate. Within this was established a Christian community at Heavitree, the oldest church outside Exeter, which would also have provided for the needs of St. Leonard’s-to-be.

Following the Norman conquest, there is no mention of St. Leonard’s in Domesday Book (1083— 86), hut the re-allocation of the royal estates found Richard of Redvers, 1st Earl of Devon, in possession of Wonford together with the Manor of Exminster. Either he or his son Baldwin is said to have built the first chapel on the site of the present church, naming it after St. Leonard, a French nobleman who became a monk and formed a community whose especial care was for prisoners. A statue of St. Leonard holding prison chains stands in the foyer of the present church. In about 1140 Baldwin founded a Priory, and “one Stephen of St. Leonard granted six acres of land to the Cluniac monks of the newly-founded Priory of St. James, opposite Salmon Pool, for the repose of his own soul and those of his parents.” The priory was closed long before the Reformation.

It was not until 1222 that parish boundaries were defined and priests settled in parish churches endowed by wealthy patrons. In 1283, Master Lucas, a priest of St. Leonard, was among twenty-one men named in an ecclesiastical intrigue resulting in the murder of Precentor Walter Lechlade on his way to early matins at the Cathedral. No indictment was made. In 1397, Bishop Stafford granted permission to “Alice, a good woman of honest conversation” to lead a solitary life of contemplation in a house in the church yard of St. Leonard. In 1407 this same good woman was left the sum of fifty shillings by the will of Sir William Bonnville, the benefactor of numerous charities and monastic houses. Some fifty years later Bishop Lacy granted similar permission to “Christine Holtby, a canoness made homeless by the destruction of the

Augustine Priory of Kildare by the wild Irish.”

St Leonard’s Church — demolished 1830

Model of St Leonard’s Church 1831-1873

In 1566 the patronage of St. Leonard’s passed from the Courtenays of Powderham to the Hulls of Larkbeare, when a new church was built. This church was replaced in 1831 and extended ten years later to meet the needs of the increasing population, but it was found to be structurally unsound within forty years and was demolished to give way to the present church. The foundation stone was laid in August 1876 by the Earl

of Northbrook, a member of the Baring family, and records his gift to the church as “a thanksgiving for his safe return from India” where he had been Viceroy and Governor for four years.

But what of the every-day life in St. Leonard’s and Holy Trinity during this long period? St. Leonard’s had remained rural whilst Holy Trinity, between the I,arkbeare Stream and the city wall, came much more under the influence of the city. Shacks and tenements had appeared against the city wall; the fear felt by those living outside the wall is understandable, as invaders attacked and plundered at intervals for centuries. Not until the coming of William of Orange in 1688 was the scene set for an era of peace and stability.

Despite the turbulence of these early times, Exeter had heen prospering as a commercial centre, particularly in the cloth and wine trades. When, in about 1311, the Courtenays of Powderhan blocked the Exe to shipping reaching the Quay at Exeter, the Topsham Road must have seen a varied procession of pack-horses, oxen, donkeys, “truckamucks” and later wagons, to and from the port of Topsham; this continued until about 1575 when the Trew canal was opened to allow small ships through to the Quay again.

Holloway Street was known as Carterne Street — the street where the carters lived and had their horses stabled. One writer describes the scene in the 18th century at the top of the steep slope from Larkbeare to St. Leonard’s Church before the road was improved to its present gradient: “At the top of the hill was a bank overshadowed by enormous elms. Upon the bank a row of peasants and waggoners was almost always to be seen,

their teams standing still, while they enjoyed their barley bread and drank their rough cider out of little barrels, which they called 'virkins'.”

In addition to Larkbeare there were three substantial merchants’ houses in Holloway Street. One, still standing, and recently occupied as “The Home of the Good Shepherd”; Holloway House (now demolished) next to Larkbeare, and Little Larkheare which stood opposite, where a garage building stood in 1982. Beyond the parish

boundary and near where Bull Meadow Road joins Holloway Street stood St. Leonard’s only “local” — the Windmill Inn, demolished about 1885; there was no pub in the parish until the Port Royal opened in the mid-19th century. The Windmill was the setting for the annual celebrations of the tuckers (or fullers) of the serge trade in the 18th and early 19th centuries, when on “Nutting Day” flags and bunting were flown, full regalia was worn, and after feasting at midday the company gathered nuts in the nearby woods, to return to dinner, home- brewed ale and merry-making until late into the night. The cost of celebrating on this special occasion was met by the masters — the workers regarding their masters’ generosity as their annual bonus.

By 1700 the “Larkbeare” establishment must have been deeply involved in the cloth trade. Maps of the city at that time show Bull Meadow and the whole area between Holloway Street arid the river, from Friars Gate to beyond St. Leonard’s Church, covered with wooden racks carrying serges stretched on tenterhooks. A writer of the period described the scene: ‘The whole town and country around for some twenty miles is employed in spinning, weaving, dressing, scouring, fulling and drying of the serges.” At the height of its cloth trade, Exeter ranked fourth in wealth among the provincial cities of England.

In 1716 the winds of change began to blow on Larkbeare. The following advertisement appeared in The

Exeter Post Boy —

A Tenement To Be Lett

Being the Fore Part of Larkbeare House, without Southgate, Exon, containing a Kitchen with a little Room by, a large Parlour and a Cellar, with a Chamber over the Cellar; also 5 Lodging Chambers with 3 Closets; likewise a Garden; being very fit for a Private Family or any one who chooscth to live without the limits of the City. You may inquire of Mr. Lavington at Larkbeare House, who is ready to treat with any Person about the same.

Ceiling at “Great Larkbear” remaining at 38 Holloway Street

On Mr Lavington’s bankruptcy in 1737, Larkbeare House with thirty-seven acres of land was sold to John Baring of Palace Gate. From this association there followed great changes in St. Leonard’s parish.

John Baring, posthumous son of a Lutheran minister of Bremen, came to Exeter in 1717 at the age of 20 to study the trade of serge-making. In 1723 he took British nationality, and in 1729 he married Elizabeth, daughter of John Vowler, a wealthy Exeter merchant. His wife’s dowry assisted him in establishing an extensive business in the wool and cloth trade; his native language served him well in Continental dealing which prospered enormously from the economic policies of William III. At Larkbeare, the Barings rapidly increased their estate by further purchases of land, together with the Rectory and Living of St. Leonard’s. Of John Baring’s social status at that time, it has been said that, in Exeter, only Mr. Baring, the Bishop, and the Recorder kept carriages.

John Baring died in 1748 in his 51st year, to be succeeded by his son John, who had the good fortune to inherit the intelligence and business acumen of his parents. He joined his brother Francis in developing the family business, through London connections, into that great enterprise of commercial banking — Baring Brothers — which finally collapsed ignominiously as recently as 1995.

Leaving the management of this business mainly to Francis, John returned to Devon to establish the Plymouth Bank, and later the Devonshire Bank (1770-1820). But whilst the Barings at Larkbeare were prospering, their next door neighbour at Mount Radford found himself in dire financial straits. John Colsworthy, an Exeter merchant, through the loss of his ships at sea was declared bankrupt in 1735. His estate, comprising the house and 17 acres of land, was bought by John Baring the second for 2,000 guineas.

The history of Mount Radford, also known as Radford Place, dates from about 1570 when Lawrence Radford, squire, an eminent lawyer, “did build him a fayre house and called it Mount Radford.” Like its earlier neighbour at Larkbeare, the house is shown on Hogenberg’s map of 1587 as having castellated walls of robust construction, and due to its excellent vantage point it was occupied for military operations against the city by Parliamentarians and Royalists in turn during the Civil War. Mount Radford’s occupants include Sir John and Lady Doddridge, whose recumbent effigies can be seen in separate alcoves on the north side of the Lady Chapel in Exeter Cathedral. Sir John was a Justice of the King’s Bench, and became Solicitor-General in 1604.

On acquiring Mount Radford, John Baring II proceeded to transform the old medieval residence into a stately red-brick Georgian mansion in a park-like setting. In 1757 he married Ann Parker, a cousin of Lord Boringdon of Saltram House, Plympton, and leaving the Larkbeare establishment in the hands of his brothers and their widowed mother (who died in 1766), he and his wife settled into the more salubrious setting of their new estate. An impressive carriage entrance was made off Magdalen Road, with a tree-lined drive following the course of the present St. Leonard’s Road. (One surviving cedar tree can still he seen by No.25 St Leonard’s Road.)

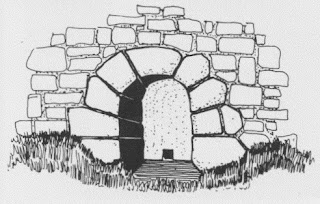

Topsham Road was diverted into a cutting away from the house and nearer the church, thereby reducing the noise of the carters and their charges, and easing the steep gradient to Holloway Street. An arched footbridge was formed over Topsham Road, giving direct access to the church; one remaining buttress of the bridge can still be identified in the stone retaining wall of the churchyard.

By the purchase from Arthur Kelly, Esquire, of the Manor and Lordship of Heavitree in 1770, almost the whole of the parish of St. Leonard was in Mr. Baring’s possession.

Mount Radford House

Foot-bridge from Mount Radford House to St Leonard’s Church

The life-style of the merchant prince of St. Leonard’s is described in Trewman's Exeter Flying Post in 1849, by Dr. Oliver who writes: “In his days Mount Radford was the abode of taste and hospitality; there, modest merit was sure of meeting with encouragement, and poverty found comfort in relief.” Mr. Baring was

Member of Parliament for Exeter in five successive Parliaments and Sheriff of Devon in 1776. He had distanced himself from Francis's London based banking operations, remaining a sleeping partner until his retirement in 1800. While Francis was involved with the slave trade, John voted for its abolition in 1796. He died in 1816 at the age of 85. In his private life, Fate seems to have been unkind. His wife died after only eight years of marriage, having borne six children including two sons, neither of whom married. The Baring line was perpetuated by his brothers Francis (lst Baronet of Larkbeare). and Charles. It continues today with descendants in six families of the nobility.

Following the death of John Baring II, the Mount Radford and Larkbeare estates passed to his bachelor son and heir, John Baring III — who sold them to his cousin, Sir Thomas Baring, 2nd Baronet of Larkbeare, in 1817. The mansion at Mount Radford was tenanted furnished until 1826, when — together with its pleasure grounds — it was sold and used as a college until 1902, when it was demolished for the development of Barnardo Road and Cedars Road.

“Great Larkbeare,” the old house and grounds on the east side of Holloway Street, had been occupied by the Barings and their business associates from 1737 until 1819, when it was leased on a number of short tenancies until sold by Sir Thomas Baring to the Misses Hodge in 1832. “Little Larkheare,” the property between Holloway Street and the river, had been leased as a residence and cloth fuller’s business to John Bowring, succeeded by his son Charles Bowring who purchased it from Sir Thomas Baring in 1824. In 1792 it was the birth-place of his son, who became Sir John Bowring LL D, , FRS etc, an eminent lawyer, scholar and Colonial administrator. Charles Bowring was one of the last representatives of the ancient woollen trade of Exeter, and saw its final decay and departure to the north.

“Flowery and bowery” elegance — St Leonard’s Road

The disposal of the remainder of the Baring St. Leonard’s estate coincided with a great building boom in the city. Selected sites were acquired by the wealthy to establish miniature estates with sizeable houses such as The Grove, Fonthill, Claremont, Leonard’s Lawn, Spurbarn, Penleonard, and the larger houses in Victoria Park Road, Lyndhurst Road and Wonford Road to the east. The remainder of the estate passed into the hands of builders, much of it to the Hoopers, for development. The difficulty in crossing the deep ravine at Bull Meadow in Magdalen Street was overcome by the building of”Magdalen Bridge” in 1832. The bridge had parapets on both sides; the north parapet was removed in the 1950s when Western Way was formed through the previously cultivated valley. Piped mains water was brought tn St. Leonard’s in 1833, and town gas followed in 1836. Mount Radford was now set to become a ‘flowery and bowery little suburb” of the Victorian bourgeoisie as described by the writer George Gissing.

The builders had arrived: Higher Terrace and Lower Terrace (now St. Leonard’s Road), Victoria Terrace (now Victoria Park Road), Albert Terrace (now Lyndhurst Road). Haldon Terrace (now part of Wonford Road), Queen’s Terrace (lower end of Marlborough Road), the houses on the south side of Magdalen Road together with the Crescent and the Quadrant — all sprang up. Full credit must be given to the builders, who were their own architects and landscape planners, for the gracious examples of domestic architecture which they have left us. A rectory was built on Magdalen Road (now Magdalen House, a home for the elderly), and shops opened on the north side of Magdalen Road to serve the new suburb, still referred to as “Mount Radford Village.” The Barings have left their name on Baring Crescent — described at the time of building as “superior cottages” — Baring Place (next to St. Margaret’s School in Magdalen Road), and Baring Terrace (off Weirfield Road).

The maps of 1773 and 1875 indicate the transformation which took place in St. Leonard’s in that century. This was followed by the building of East Grove and West Grove Roads on the breakup of the Grove Estate, together with Barnardo Road and Cedars Road. The terraces of smaller houses between Fairpark and Holloway Street were built in the 1890s to house workers in industry, railways and public services which had increased employment in the city. The Friars and the Colleton area in Holy Trinity parish had changed too. The cloth racks had given way to Friars Walk and some fine stuccoed merchants’ houses. Also came the admirable red-brick terrace of Colleton Crescent, built by Nosworthy 1802—1814, standing high above the Quay with a magnificent panoramic view across the river, until the gas works and railways arrived on the scene. Between 1825 and 1827 the canal was extended to Turf, allowing vessels of up to 400 tons to come to the Quay; this brought increased trade, requiring the building of the cellars and two fine warehouses in about 1835.

Nearer the city, also in Holy Trinity Parish, lay Southernhay which had remained as pasture-land as late as 1782 except for the building of the Devon and Exeter Hospital (1741-43). This has become Dean Clarke House, named after its founder Alured Clarke Dean of Exeter, following the building of the new Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital at Wonford (1968-4). Between 1790 and 1819 Nosworthy built the Georgian brick terraces, which complement the stuccoed terrace with its Doric colonnade on the east side, and Southernhay House, an outstanding example of a large private house of the period. The houses were graced with a park-like central oasis surrounded by iron railings, removed for use in World War II — since when the City Council has maintained the area for the use of the public.

Southernhay House, Southernhay East

“Burnet Patch” bridge from Southernhay

Progress demanded that the old should give way to the new; the city wall was breached to form “New Cut”

between Southernhay and the Close below the “Burnet Patch” iron footbridge dated 1814, and the Great South

Gate was demolished in 1819, together with Holy Trinity Church built close against it. In the same year a

contract was signed for the re-building of the present church, which was consecrated in 1821.

Many of the new Victorian houses of St. Leonard’s, Colleton and Southernhay were occupied by the families of serving and retired naval and military officers and civil servants, who found in Exeter a relaxed way of life away from the exploits of Empire building. Professional and businessmen of the city and wealthy newcomers also found the new suburbs had much to offer in good living. Servants lived in at low wages and tradesmen were at the housekeeper’s door with the best of Devon produce at highly competitive prices. Then would be heard the “clip-clop” of the well-groomed butcher’s cob or tile wheels of the dairyman’s float with its polished brass churn. Cabs stood on call at the end of the road, and a horse-drawn water- cart laid the dust on hot summer days. Bootscrapers at the front doors were a necessity as well as being fashionable, for the horses were unpredictable, and droves of cattle or sheep bound for Exeter market by way of Magdalen Road or Holloway Street were quite unaccountable . . . the ladies’ crinolines were in constant danger!

Gracious architecture — St Leonard's Road

George Gissing’s Born in exile is set partly in Exeter and its surroundings. He came from London in 1891

to live for a while at No. I St. Leonard’s Road, where lie was heard to exclaim — “Every morning when I

wake I thank heaven forr silence.” But he also complained of Exeter by saying “Intellectually it is very

dull” — perhaps the new bourgeois existence had dulled the Exeter intellect!

The Victorian way of life continued with little change up to World War I, in which Exeter suffered no

material damage; but after the war, in a more stringent economy and with stress on improved circumstances

for the workers, the era of “fair shares for all” had arrived. The old slums of the West Quarter, which

lay in Holy Trinity parish, were demolished to give way to new tenements. In St. Leonard’s residential

development took place at Spurbarn, Penleonard, and in the area between Topsham Road and the river.

With tarmacadam roads came the motor car and its demands for better and wider roads; Topsham Road was

widened throughout its whole length. The large rectory in Magdalen Road was given up in 1941, when

“Rockleigh” in Matford Lane, a dower house of Fonthill, became the present rectory. Fonthill was

demolished in 1960 to make way for houses; its entrance lodge still stands in Wonford Road.

In World War II St. Leonard’s and Holy Trinity took their share of the German hombing of the city in May

1942. In Southernhay West, the terrace north of Bedford Street was destroyed; the design of its successor

(which does not conform to the height and character of the surviving Georgian architecture) has been the

subject of much controversy. In Magdalen Road, shops and houses were destroyed in “the village” and in

St. Leonard’s Road can he seen the replacement villas where bombs fell. It is a pity that the 20th century

architects were not more sympathetic to the elegant creations of the master-builders of the 19th century.

Parker’s Well House — where the Central Schools now stand — was completely demolished by a high-explosive

bomb; Mr. Bill Turner of West Grove Road recalled in 1982 having assisted in building a huge bonfire on the roadway

nearby with timbers from the remains, to celebrate victory in 1943.

During the four decades since World War II, good quality houses have been built in the grounds of larger

houses where gardeners can no longer be afforded to maintain the standards of the past, and the attractive

prices of building land have become irresistible. Some large residences have lent themselves to

institutional and business uses, such as homes for the elderly, language schools for overseas students, a

publishing house, an hotel, and offices; whilst others have been divided into smaller living units. The

re-generation of the Friars area off Holloway Street ts a welcome improvement. This area and the many

other contemporary developments which have taken place will be reviewed in the “walks” which follow this

introduction.

In attempts by the statutory bodies to deal with traffic problems, much demolition of buildings and re-building of roadways has taken place since 1960 in the area of Southgate, Holloway Street and Magdalen

Street, and regrettably a number of buildings of historical and architectural interest have been lost

despite many protests.

In 1973, the City Council put forward proposals for a massive road development scheme which would have virtually wiped out Bull Meadow pleasure park and changed the whole character of die area. Fortunately, determined opposition from the residents, backed up by St. Leonard’s Neighbourhood Association and Exeter Civic Society, resulted in the abandonment ol the scheme following a public inquiry. St. Leonard’s has seen no substantial replacement of industry since the decline of the cloth trade arid shipping at the Quay. The mill at Trew’s Weir has functioned since its transition from cotton-milling to paper-making in 1835. The establishment of the Maritime Museum at the Quay and across at the Basin has given new life to this area in providing leisure-time activities for the city’s residents and vistitors. The City Council plans to maintain the canal as a recreational amenity in conjunction with the Maritime Museum.

View from South Gate —pity the poor pedestrian!

St. Leonard’s is designated by the City Council as a Conservation Area. Under the relevant Central

Government Acts the protection of listed buildings, the control of demolition, and tree preservation are

matters which should be carefully watched over by residents to preserve their heritage and ensure that

what they cherish is passed on for future enjoyment. The Civic Society and the Neighbourhood Asociation

support the residents to this end. Strong representations were made to the City Council in 1979

when, in Wotiford Road, granite kerb-stones and channels were being replaced by concrete. Following this

incident, a survey of street furniture was made by the Civic Society in co-operation with the City

Conservation Officer.

In the preface to his book, Two thousand years in Exeter” (1960) W.G. Hoskins, our native contemporary

historian, author television broadcaster and a resident of St. Leonard’s for many years, writes: “Paradise

itself can be no better than Exeter on a summer morning; but even Paradise, no doubt, has some small

faults.” St. Leonard’s is indeed a part of that Paradise. With great appeal to its residents, it offers

much of interest to those who may care to explore it.

Our heritage at South Gate — 1982

Walk No 1

The western area of St Leonard’s

between Holloway Street / Topsham Road and the river

The medieval South Gate, demolished in 1819, is commemorated by a plaque fixed to the boundary wall of the

former Holy Trinity church in South Street. Through the gate passed visiting monarchs to the city on the

direct route from London by way of Magdalen Street. The gate structure included two prison wings — the

west wing held the felons, the east wing held the debtors; both wings are described as having been foul,

dark and damp. Remains of the Roman south gate can he seen some 25 feet west of the medieval gate position.

The first building on the left in Holloway Street abutting on to the slip road from “The Acorn” is

basically a large 18th century merchant’s house, which was extended and adapted as “The Good Shepherd

Hospital,” a home for mentally retarded women until the 1970s. It has some interesting features on its

front elevation. Plans have heen prepared for its re-hahilitation as dwelling units. The group of Georgian

and Victortan style buildings on the right of Holloway Street were spared demolition for road improvement

on account of their architectural merit, especially the centre “Egyptian” house.

Below the neat Edwardian terrace on the left is the former St. Nicholas School, a Roman Catholic founded

State school huilt in 1875, and re-housed on its Matford Lane site in 1977. The old school

buildings have been divided and adapted for use by Exeter Gymnastic Club and Jehovah’s Witnesses. Next

comes Lansdowne Terrace, an imposing group of late Georgian style dwellings that suffered neglect for many

years, and are now being restored. On the other side of Holloway Street are dwellings recently erected in

the re-hahilitation of the Friars area and Melbourne Street.

At the bottom of Holloway Street on the left at No. 38, adjoining the Post Office, is all that remains of

the ancient Larkbeare Mansion mentioned in the historical introduction. It was the victim of extensive demolition in

the late 19th century when Roberts Road was made and Holloway Street was widened. Built of red Heavitree

stone, its north and east exterior elevations bear some interesting relics of its construction. Its

interior holds an unusual timber and plaster panelled ceiling in the ground floor room, moulded

plasterwork and a stone fireplace on the next floor, and the roof construction can be seen in a

delightfully re-furbished room on the top floor. The house was saved by Exeter City Council from

demolition. With grant aid from the Devon Historic Buildings Trust, extensive repairs and restoration took

place in 1979. It is now inhabited, and by arrangement it may be visited by those genuinely interested.

The dilapidated cottage, coach-house and stables now seen across the road were built to serve the present

“Larkbeare” mansion. They and the adjoining garage building are on the site of the dwelling and warehouse

of’ Little Larkbeare.,” referred to in the historical introduction. A quaint hexagonal gazebo, now sadly

neglected, standing in the grounds of the present “Larkbeare,” is the sole relic of the former residence.

Along Topsham Road, standing in grounds behind a fine limestone masonry wall on the right, is “Larkbeare,”

a country-style mansion built of limestone in about 1870 by John Charles Bowring, wealthy son of Sir John

Bowring. The house and grounds were bought by Devon County Council in 1876 for use as Judges’ Lodgings,

alternating with a day-time High School; the holding of the Assizes fell within the school holiday breaks.

This arrangement continued until the begining of World War II, when Larkbeare became the administrative

offices of Devon County Education Department. In the early l960s, following restoration work, it was again

occupied as Judges’ Lodgings.

“The Larkbeares,” Holloway Street

Between Larkheare and St. Leonard’s Church lies Larkheare Road leading down to the riverside. Known in the

18th century as Larkbeare Lane, it served the lime kilns at St. Leonard’s Quay; the site of the kilns now

lies within the grounds of Larkbeare. The kilns were in operation for about 140 years. Limestone from the

Babhacombe quarries and coal from the ‘Welsh pits to fire the limestone were shipped to the Exe estuary

and brought up the canal by barge to the lime quay.

The parish archives record that in 1739: “After ye Lirnekilns had been built some years, it appear’d that

ye ffootway in St. Leonard’s lane, leading to ye Church-yard, was going to Ruin, as likewise ye Hedge

which parted ye said Lane, and ye Plot ajoyning ye Church-yard belonging to ye Rectory was in Danger of

being demolish’d.” The outcome was the building of a new wall to the church-yard,

and the laying of a new footpath to the church gate.

The progress of St. Leonard’s church through the ages has been followed in the historical introduction. The building of the present church in Victorian Gothic style was commenced in 1876, and on completion in

1884, was consecrated by Bishop Frederick Temple. The spire — 145 feet to the top — was the gift of Mrs.

L. A. Miles of Dix’s Field, in memory of her husband William Miles.

St Leonard’s Church

Between Weirfield Road and Bungalow Lane is the former site of the Royal School for the Deaf, now known as the Deaf Academy, which moved to Exmouth in 2020. The site is being developed for housing and a care home. The school had its origin as a

private institution at Fulford, near Crediton. In 1828 by means of public

subscriptions a new building was erected in St. Leonard’s on a site of about two acres lying within the

confines of the present establishment. In 1873 “twenty-eight boys and as many girls receive all the aid

which kindness and skill can render to the deaf mute.” A large-scale building programme took place in the

l960s, and in 1981 about 80 boys and 60 girls received full-time instruction there. The playing

field, connected to the school by a foot-bridge over Topsham Road, is a remnant of the lawns of Mount

Radford House. The enclosure is still shown on the Ordnance Survey map as “Mount Radford Lawn.”

The Baring Family Memorial, St Leonard’s Church

TO THE MEMORY OF

JOHN BARING of LARKBEARE who died 1748 aged 92

ELIZABETH VOWLER his wife who died 1766 aged 64

and of their children

THOMAS VOWLER BARING who died 1758 aged 25

and

JOHN BARING of MT RADFORD who died 1816 aged 85

and of ANN PARKER his wife whoe died 1765 aged 36

also of their children

ANN who died 1804, ELIZABETH who died 1805 and

FRANCIS who died 1810

all of whom lie buried in the adjacent Churchyard

This monument is erected by

Francis George 2nd Earl of Northbrook

Francis Denzil 5th Baron Ashburton

John 2nd Baron Revelstoke

Evelyn 1st Earl of Cromer

descendants of JOHN and ELIZABETH BARING

1913

Parker’s Well House derives its name from the spring of water in Matford Lane. The Devon County Central First and Middle Schools and St. Nicholas Roman Catholic School were re-established on the site of the former Parker’s Well House in the 1970s, on the closure of their former buildings off Preston Street and Holloway Street. St Nicholas School moved to Ringswell Avenue in 2018 and the First and Middle Schools, now combined as St Leonard's C of E Primary School, took over the entire site.

Next to “Coaver”, the picturesque Queen Anne style residence “Bellair” stood in its private grounds; the major portion of the house has been preserved and is attached as an annexe to the Council Chambers of County Hall.

Parker’s Well, Matford Lane

Facing Topsham Road and giving its name to Bungalow Lane, [now renamed Trew's Weir Reach - requires updating] is a single storey dwelling of interesting appearance far different from the usual run of bungalow creations. About here stood the Mount Radford toll house and turnpike gate, both removed in the late 19th century. On the angle of Topsham Road and Matford Lane, the ceremonial entrance to Devon County Hall passes between a pair of fine Dartmoor granite pillars originally set up for the entrance gates to “Coaver”. Entering the grounds to view County Hall, the frontage of “Coaver” is seen on the left, once a private residence of late Georgian design. It now serves as a social and conference centre for the staff of Devon County Council.

Mount Radford Turnpike Gate, by G Townsend (about 1875)

The last private occupant of “Bellair” was Dame Georgiana

Buller, remembered for her interest in the establishment of St.

Loye’s College for the training of disabled persons. The good

lady intended to bequeath “Bellair” to St. Leonard’s Church for use as a rectory, but she died in her sleep the night before this

arrangement was to be made. She is remembered by a blue plaque on the building.

County Hall and “Bellair” — ceremonial entrance

"Bellair” — west front

County Hall — detail of ceremonial entrance

By the acquisition of “Coaver” and “Bellair”, Devon County Council held a park-like estate in which to

build the new County Hall. It was built (1958-63) by Staverton Builders of Dartington to the design of

Horace McMorran, a London architect. The interior of County Hall contains some good- quality joinery and

finishings; the panellings in the Council Chamber and Committee Rooms, worked in a variety of native Devon

woods, are of a particularly high standard of

craftsmanship.

After crossing the County Hall car parks, turn left into Topsham Road, passing the residences of the

1930s on the right and a pleasant terrace of late-Victorian houses on the left, followed by a number

of older villas of Georgian style. Across the way, the single tile-hung dwelling standing forward is the

lodge of “Abbeville,” a large house that was demolished to make way for the present group of dwellings for

the elderly. On the left is the Buckerell Lodge Hotel, described in its brochure as “originally the

country seat of a Regency Squire.” It was a large family house of the early Victorian era in a style

similar to others in the outer suburbs of the city.

Turn right into Salmon Pool Lane, where on the left hand side is an interesting group of dwellings in

pairs, designed by architect Louis de Soissons, and built by Staverton Builders of Dartington in the

l930s. On the right, are post-World War II houses with a pleasant arrangement of style and vista into

Knightley Road.

At the lower end of Salmon Pool Lane, turn left to Abbey Court, a 1960/70 group of flats with a well-designed terrace at the riverside overlooking St.James’ Weir and the Salmon Pool, which can be reached by

a bridge over the mill leat. St.James’ Priory, referred to in the historical introduction, was in this

vicinity. Turn back and follow the footpath between the river and the rear gardens of houses on Rivermead

Road. “Belle Isle,” the City Council’s nursery, lies on the left opposite Bungalow Lane. The path on the

left leads to the suspension foot-bridge over the Exe built in 1935. Previously, the crossing of the Exe

in this vicinity had been by boat above the weir or by ferry at the Quay.

The “Old Match Factory,” lying between Weirfield Path and the river, bears the date 1774, and a lucifer match factory is mentioned in this area on the 1851 census. In the 1850s it was a flax mill known as Lower Mill. It became an annexe of the Trew’s Weir paper mill, and has been used at various times By John Pitts &

Sons for stabling horses, paper-bag making, storage of materials, and as a Social Club for mill personnel.

A little further along the path, the scene is dominated by Trew’s Weir; originally formed of stakes and

brushwood, it was known as St. Leonard’s Weir. In 1563, John Trew of Glamorganshire was commissioned to

restore the means of navigation to the Quay at Exeter. Instead of removing St. Leonard’s Weir arid clearing the course of the river as intended

Trew was authorised to construct the Exeter Canal which involved the rebuilding of the weir which bears

his name. In addition to providing water

for the canal, the weir has supplied power to industry. In 1633 George Browning “as in trouhle with the

Canal Authority when he built a fulling mill just below the weir. The mill leat was faulty and lost much

water to the canal; Browning was ordered to close the mill in 1670.

Industrial activity in this area in the following century is obscure. A lease of a field adjoining the weir

was granted by the City Chamber to Robert Tipping in 1793, with permission to build a weir arid a mill,

“not for grist, or lulling, or spinning worsted cloth”. A cotton-spinning mill was established which, in

1795, is said to have employed some 300 men. The mill closed in

1812 and was later inspected by John Heathcote, driven out of Loughborough by the Luddite Riots, but he

decided it was more economical to set up his machine-lace business at Tiverton, and this he did in 1816.

The disused cotton mill served as tenement dwellings until it was adapted for paper-making in 1834. With

changes of owners and up-dating of machinery, it came into the ownership of John Pitts & Sons in 1907. In the early 1980s it produced, from waste, mainly wrapping papers and pasteboard materials. The mill closed in 1983 and the main building has been converted to apartments.

Leaving the mill, the next turning to the right leads into Weirficld Road. A short distance up on the

right is Baring Terrace (formerly Weirfield Terrace), an early Victorian group of four dwellings erected

for occupation in conjunction with the mill. Allowed to fall into disrepair for some years, it was restored for re-occupation in the 1980s. The group of dwellings nearest the river were built in the l960s to

replace older houses extensively damaged by flooding in 1960. Next, alongside the path, stands the Port

Royal Inn, a mid-Victorian arrival at the riverside, and a pleasant setting in which to enjoy a

“sundowner.” Behind the inn is Exe House, an interesting villa of the Victorian era, at present somewhat

neglected.

The Exe and Trew's Weir from the Suspension Bridge

The outfall of the Shitbrook stream into the river can be seen at the foot of Colleton Hill. A short

distance up the hill on the right is Colleton Grove, from the end of which can be seen in the grounds of

Larkbeare the old gazebo previously mentioned. The large recess formed below the cliff at the end of the

Quay by Colleton Hill was used as a ballast store for the shipping trade.

Continue along the main Quay with its unusual iron bollards, said to be cannon barrels from the Battle of

Waterloo, and intended to be set up at the Wellington Monument, in Somerset. The brick arched cellars

tunnelled into the face of the red cliff are said to have been used for the storage of petroleum and

petrol when first imported.

The pair of five-storey stone warehouses built in about 1835 by the Hoopers and R.S. Cornish — who were

prominent Exeter builders — are outstanding examples of industrial architecture of their time. Under the

canopy of the open-sided fish market opposite is “The King’s Beam,” a cast iron structure dated 1838 and

made by Bodleys, ironfounders in Exeter (1790— 1967). The beam was used by the Customs Authority for

suspending weighing scales.

Houses on Colleton Hill

The Custom House at the Quay

The Quay at the filming of ‘The Onedin Line’ BBC-TV

from an etching by P V Pitman

25

The Custom House dated 1681 and still in use by H. M. Customs & Excise, is reputed to he the first brick building in Exeter. The arches on the front were originally open, forming a covered way, and the upper windows had leaded lights similar to those on the rear of the building. It is listed as an ancient monument, and it contains some excellent examples of ornamental plaster ceilings by the Devon craftsman John Abbot. Nearby, among the smaller stores and workshops is the attractive little Wharfinger's Office, built in 1778 to house the city’s harbour-master. Also in this picturesque setting is the Prospect inn. The mid-l9th century dockland atmosphere of the Quay was recognised by the BBC as unique for filming scenes for the “Onedin Line” television series in the l970s.

Continue the walk on the pathway climbing parallel to the City wall, noting the repair of the breach in the wall with alien red brick which caused public outrage at the time. The wall, here, presents a good study of the variety of stones used in its construction. Cross the grassed area opposite the brick patch in the wall, and pass between the block of flats and Acacia House, Magnolia House, and Lawn House above on Friars Green, to reach the lower end of Friars Gate. These three houses are distinctive in character, set in their pretty town gardens. Colleton Villa is a well-proportioned building in the Greek Revival style, and it is complemented by the design of the block of residences across the way, completed in 1982.

The graceful lines of Colleton Crescent

The building of Colleton Crescent has been referred to in the historical introduction. Its soft-red

brickwork, decorated Coade stone door surrounds and white-painted relief in bands and cornices give a

well-balanced elevation with added interest in the ironwork of the balconies and railings. Internally

there are good examples of geometrical staircases, pine panelling and moulded plasterwork in rooms of

generous proportions. Costly to maintain as private residences, it is sensible that they are used and

well-maintained as prestige business houses. Nearby in Melbourne Place are good examples of large stuccoed

merchants’ houses of the early 19th century — Colleton Lodge, Friars Lodge, Colleton House, and Southview.

Towards Holloway Street turn left into Friars Walk; on the left are pairs of early Victorian stuccoed

houses with interesting features worth preserving. The recent meeting-house of Jehovah’s Witnesses set

behind its little forecourt could be transformed by restoring its frontage details to the original. The

Salvation Army Temple was opened in 1890, following years of unemployment and near-starvation in this area

of the city — relieved by the good work of Exeter’s Salvationist “Angel Adjutant,” Kate Lee. The solid

brick-clad citadel underwent extensive re-furbishing in 1977/78.

“South View” and the Hour Glass Inn, Melbourne Street

Across the way is the former Holy Trinity Church Hall; erected in 1913 it became redundant on the closure of the Church in 1969, since when it has been used by youth organisations. At present it is leased by St. Leonard’s Church to the International School, Wonford Road, as a recreational centre for its students. The Friars Gate area has seen some extensive rehabilitation in new blocks of flats built by the City Council from 1960 onward.

This walk ends near the point of starting, by South Gate.

South Gate from South Street, about 1800

Walk no. 2

The eastern area of St Leonard's

between Holloway Street /Topsham Road and Magdalen Road

At South Gate, hugging close to the city wall, is the former Holy Trinity Church, referred to in the

historical introduction. Built of stone with a stuccoed exterior finish, the structure fell into disrepair

before its closure in 1969. It received ill-treatment from vandals until taken over by ex-Navy personnel

in 1977 and adapted by voluntary work as their White Ensign Club.

Follow the footpath beside the city wall to Trinity Green, a former burial ground now a car park; the

garage buildings hacking on to the wall were once the mews for the Southernhay residences. The grounds of

the Bishop’s Palace lie behind the city wall, which appears to have been re-built at some time in

Heavitree stone with replicas of former bastions — one of which, known as Bishop Robertson’s Barbican,

carries his blazon above the entrance door.

Across on the east side of Southernhay is Dean Clarke House, formerly the Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital,

now used by the Devon Health Authority. The architect and builder were one and the same, John Richards;

born at Mariansleigh, a village in North Devon, he trained with a master-builder in Exeter and acquired a

genius in geometry and architecture. The well- proportioned Georgian-style frontage is scheduled as of

architectural merit.

Bishop Robertson’s Barbican, Trinity Green

Tile terraces of elegant houses must have presented a very different picture iii the mid-19th century

when occupied by the families of military and naval officers, physicians, lawyers, clerics and literary

men. Top hats, flock coats and crinolines must have abounded, and creature comforts were the care of

housekeepers, maids, coachmen and gardeners, whilst nursemaids paraded their bassinets on the velvet green

of their railed-off sanctuary.

Leaving Southernhay by way of Barnfield Road — the Barnfield Theatre is on the right. Sponsored by the

Exeter Literary Society, its foundation stone was laid in the Society's jubilee year, 1890, by its

President, Lord John Coleridge, Lord Chief Justice of England. Used for many years as a public hall, it

served as a communal centre in a ruined city following World War II. It was later adapted for use as a

theatre and concert hall to seat about 300, and in that role is much used by amateur Arts Societies.

Doorway with Coade stone dressings, Southernhay

Across the road is Barnfield Crescent, another fine example of the work of the architect/master-builder

Matthew Nosworthy, in similar style to Colleton Crescent. Designed and used as private residences In the

19th century, the Crescent is now occupied as offices and consulting rooms.

Finance House, at the junction of Barnfield Road and Western Way was erected in 1976, adding nothing to the

architectural merits of the neighbourhood. Further construction of “office blocks’’ is in progress on

gardens hacking on to this building.

Crossing Western Way by the traffic lights, continue along Barnfield Road to Denmark Road. The terrace

of houses on the left form a pleasing group with their frontages faced with Portland stone masonry, unusual

for Exeter. The course of the Shitbrook Stream lies below the City of Exeter bowling green, set in its

hollow, well below the roadway across the former valley. Next to the bowling green, at the road junction,

is the memorial to martyrs of long ago — Thomas Benet, MA, who was burnt in Exeter in 1531, and Agnes

Prest who was burnt in 1557 — their crime being that they “refused to accept the doctrine of

transubstantiation.” The memorial was erected in 1909.

[checked to here]The Maynard School for Girls stands in well-planted grounds across the way. Founded by Sir John Maynard (1602— 1690), Sergeant-at-Law, a Commissioner of the Great Seal, and a famous lawyer of his day, he lived through six reigns and the Commonwealth. The school carries his coat ,,f arms in its blazon.

Georgian doorwqv, BarnJield Crescent

St. Matthew’s Vicarage, re-built following the destruction of the former vicarage in World War II, is a near neighbour of Maynard School, sharing the same rectangle. Denmark Road has an interesting variety of the larger Victorian family homes, between which can be seen east end views of the Cathedral and its towers. By a short diversion into Spicer Road, “The Lodge,” a home sponsored by the Distressed Gentlefolks Aid Association, can be seen.

St. Mary Magdalene Almshouses, at the] unction of Denmark Road with Magdalen Road, form an interesting group in their setting of cedar trees. Built in 1863 of Pocombe stone with a boundary wall and entrance feature of the same, twelve dwellings replace accommodation of former St. Mary Magdalene Hospital which lay near Bull Meadow, and the group of four replace Palmer’s Almshouses whose site is recorded in Magdalen Street. The old Hospital, shown on Tozer’s map of 1793, was founded during the time of Bishop Bartholomew (1161—84) to care for lepers.

Below, in North Park, is a more recent group of twelve homes for the elderly, and in Fairpark Road, William Hurst — five times Mayor— is remembered for his almshouses, rebuilt in 1928 and 1958; these, with a block given by Margaret Kathleen Trump, provide twenty homes for the elderly. Ernshorough House, nearby, was built in the late 19th century as a private residence. Following World War II it was used for many years as a geriatric hospital, and in 1980 it was adapted to flats, including a new annexe in its grounds.

Plaque at St Mary Magdalene Almshouses, Magdalen Road

Continue up Magdalen Road past a group of early 19th century stuccoed villas, a pair of which (Nos. 12 and 14) have a lateRegency style of craftsmanship in their porches and Fretted eaves.

The three-storied terrace of cream brick opposite, with its upper bay windows and gabled dormers built in the early 1900s, is complementary to the older houses and forms an interesting contrast to the early Victorian assortment of brick and stucco styles which had stopped at the Post Office. The shops in this latter group were evidently designed into the buildings; the cast- iron slotted inserts in the granite kerbs of the public footpath are evidence that metal standards were engaged in them to support canvas shop front canopies prior to the introduction of extending roller canopies.

W:HUB STE Esq who was five Times Minr thiç City 1 DLX viii by Plaque at [I Huts/c Alms/to uses, Fairpark Road

Crafismanship in wood — &z4y Victorian, 14 Magdalen Road

The two large corner houses (Nos. 16 and 18) on thejunction with Wonford Road were thr many years the houses and surgeries of medical practitioners. in the former surgery of No. 18 is a mask of Hippocrates, the Greek “Father of Medicine.” A diversion into Wonford Road and return, presents an interesting group of Victorian villas of varying character. The house set next to No. 18 (see above) was introduced in 1980, and is a good example of design complementary to its neighbours.

In Radnor Place on the left offWonford Road, attached to Radnor House is what was once a religious meeting room of sizeablc proportions, with some moulded plaster work on its walls. It is now in use as a store for the adjoining glass works. A centenarian lady of the parish, Mrs Fear, remembers it as “Harris’s Rooms,” In which she attended Bank of Hope and Band of Mercy meetings as a child in the l890s, the former being a temperance movement and the latter taught “kindness to dumb creatures.”

Further up Magdalen Road, the introduction of new brick-built shops with living accommodation over, and the block of flats set back across the way, replace World War II casualties. The Mount Radford Inn on the corner at the road junction recalls the influence of the former Mount Radford establishment on the neighbourhood. In Victorian days and up to World iVar I, on an area near the Inn large enough to be termed “The Village Square,” stood horse-drawn cabs with a little shelter for the cabbies on call for nearby residents.

Who is this, high above the chemist in Magdalen Road?

Along St. Leonard’s Road, following the route of the drive to the Barings’ former Mount Radford House, can be seen a varied collection of Victorian villas, undoubtedly the subject of George Gissing’s reference to a ‘flowery howery little suburb.” The replacements of the casualties of World War Ii are evident - some less incongruous than others. Return to Magdalen Road, to find — set back below the garage and filling station, St. Leonard’s Lawn (No. 40), one of the larger houses (1mw divided) built on a selected site following the break-up of the Baring estate.

Across on the corner of St. Luke’s playing field at the entrance to College Avenue — and shown on the Ordnance Survey map — is tIle site of Magdalen Gallows, set (as was the custom) on a busy route to and from the city to remind passers-by that crime had its penalty. At this same spot is a circular-headed granite boundary stone marked H/P dated 1897, and beside it is a rough-hewn granite gate pillar, a relic of a farm gate in the vicinity.

Marlborough Rtjad, opposite, is mostly of early 20th century residences of brick construction, with some decoration. Awsland” on the corner, formerly a private residence, is now a home for elderly persons and “Magdalen House,” next up, formerly St. Leonard’s Rectory, likewise. in the grounds at the rear of Magdalen House is a group of recently-constructed single-storey dwellings for the elderly — Magdalen Gardens.

Passing St. Luke’s playing fields on the left, next on the right is Hensleigh House, divided into dwelling units. Its former coach- house stands close against Magdalen Road, with the road’s name set in the wail in tiles; it retains its loft door through which hay for the coach horses was delivered.

A walk into Baring Crescent is well rewarded by the sight of its elegant atid well-proportioned houses, mostly unharmed, and well maintained In their generous setting.

Next in Magdalen Road on the right is Penieonard House, typical of the early Victorian era — to be followed by the pair of Penleonard Villas of a slightly earlier period. The grounds of the larger adjacent houses lying to to the west were built over between World Wars land 11 with good quality detached houses to form Penleonard Close (approached from Lyndhurst Road.)

St. Margaret’s School is in a former large residence with adjacent houses as annexes. Baring Place, the next group, in mellow Exeter brick built in 1812, has a well-proportioned elevation in Georgian style, and is in pleasing contrast to its well- preserved Victorian-style right-hand neighbours in use as private hotels. The large residences across the way in Manston Terrace came early in the 19th century. The building of flats at Bredon Court and Francis Court in the grounds of these larger ht,uses took place in the l960s. Return to Magdalen Road past No. 78, a well-proportioned residence in Georgian style, with neighbours built in the 1930s.

In Victoria Park Road, on the right-hand side are fine examples in variety of the larger early Victorian family residences; the house at thejunction of Lyndhurst Road is of near-palatial proportions. On the left are well-built residences of the 1930s. A row of lime trees behind iron railings forms the boundary of Exeter School, seen in the distance beyond its playing fields, The school, established on its present site in 1880, was btnlt to the design of the architect Butterfield. Across the road are the courts of the Victoria Park Tennis Club. ‘Ihe woodland trees, railings and slatted wood park fencing at this end of the road give the atmosphere of a country estate.

Turning left into Wonford Road, note the Edward VII cast Iron letter box set in the Heavitree stone boundary wall, of which there is a long stretch on this side of the road. Across the road lies the Madford (original spelling) estate; its Elizabethan manor house is seen through decorated iron gates set in a high boundary wall. Built in about 1600 by Sir George Smith, thrice Mayor of Exeter, and M . P. in 1603, the house — probably thatched originally — stood in its lands forming a rectangle with no intruders until Bellair, Coaver and Gras Lawn appeared on the scene, as shown on the maps; thereafter, the whole estate has been built over.

Towards Barrack Road on the left is the Nuffield Hospital, built in 1963 by the Nuflield Trust for the use of private patients. Across the road is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, erected in 1973. Next to it is the Princess Elizabeth Orthopaedic Hospital; established in 1927 primarily for the treatment of children, the hospital has developed extensively and now provides treatment for all age groups under the National Health Service. ‘l’he hospital stands on the site of “Gras Lawn,” a large residence now absorbed into the hospital buildings, with much of its grounds in use as playing fields by Exeter University. This site was thr long known as Buckerell Bore on account of its profuse water supply, evidence of which can be seen in the “sinks” corner of Exeter School field. On Barrack Road, at its junction with Buckerell Avenue, is the head-quarters buildings of the Devon Army Cadet Force.

Exeter School

Return along Wonford Road, passing Mount St. Mary Roman Catholic School for girls occupying two former large Victorian residences, with more recent extensions In their grounds. Across the road, on the corner ofMatlhrd Road is Mamhead House, named after Lord Mamhead, Member olParliamcnt for Exeter in the 1920s, and endowed by Dame Violet Wills as charity homes.

In Nlatfhrd Lane, on the right, is St. Leonard’s Rectory looking very solid In its grey limestone masonry, and next to it comes an interesting group of early Victorian gabled houses, one of which is daringly embellished with a bay window in cream bricks, so stylish in the Edward VII period. At this point the rural nature of Matford Lane which existed for so long can still be detected. A view of the gables and chimneys ofClaremont’, in a style beloved by the early Victorians, can be had from the rear entrance road of County Hall, looking across Matford Lane.

“Bellair Villas,” Wonjord Road

Return to Wonfbrd Road, passing the iodge offbrmer Fonthill House (in the left, and a group of early Victorian houses (Ièrmerly Haldon Terrace) on the right. Opposite are dwellings of (he l93Os, followed by “Bellair Villas’’, a pair of early 19th century stuccoed houses with their gables flanked hy decorative eagles. Alongside in a cul-de-sac is Park Place, a terrace of interesting variety, and across the way is St. Petrock’s Close, a group oi’föurteen charity homes fbr the elderly, built on a casualty site of florid Var TI, as were the two corner houses at thejunction with St. Leonard’s Road. I xuiking up St. Leonard’s Road there can he seen a large Cedar of Lebanon tree, a relic of the Baring park planting.

Following down St. I sonard’s Road, the early Victorian houses stop on the left at tile footpath leading to East and Vest Grove Roads — terraces which, with that on St. Leonard’s Road, were built over tile site of Grove Hi )use and its grounds in tile earl 1900s. On the right—hand side, the three houses comprising ‘Woxihaves” form an interesting group of homes for the elderly, lollowed liv Edwardian hrick houses and a number in variety, following around into St. I etjnard’s Place, of tile first individual houses built on the Baring estate. From this point one can appreciate the fine view oI’the Haldon Hills commatided by the former Mount Radford House.

Old cedar tree — St Leonard’s Road

No. 56 St. Leonard’s Road, a large house with a forecourt, was in use as Mount Radihrd School, a private school for boys, from 1868 until its closure in 1968. Its large playground at the rear extending to Radford Road was built over in the l970s to form ‘inc Close, so-named after Mr. Vine, a headmaster at the school for many years. The house is at present in use as a home for incapacitated persons.

Returning again to Wonford Road, the change in style from Nos. 34/40 to Nos. 42/46 is well-related. Across the way at No. 7, a classical front of Greek-revival style is followed by the Quadrant, an architecturally wcll-halanced group of residences with a generous forecourt and granite entrance pillars. The Crescent originally comprised six large houses, well-designed around a central reservation enhanced by a planting of long-standing woodland trees. No. 6 has heen replaced by Crescent Mansions, a purpose-built brick block of thirty service flats fbr short-term residents. Two of these large houses are occupied by language schools for overseas students, another by a publishing press. At this point the buildings of the early Victorian era end, and below in brick-built terraces is the creation ola later Victorian era.

Nat. 38/40 Wonford Road

Continuing down Radford Road, on the left is a converted pair of small cottages, the surviving relic of Mount Radford Square — a group of cottages which, no doubt, once housed retainers of the Mount Radford estate. The old converted coach-house on the right was used in the 1960s as a work-room for making clothes. And so, into the terraces of the 1890s, built at that time by the score for the workers, on land acquired by the Freehold Land Society. The dwellings, built at a cost of less than £200 each, were let at 2s. Sd. (l21/2p) to 4s. Sd. (22½p) per week according to size. Since World War II, many have passed into owner- occupation at a price ofl 000 and under in 1950, at around £2,000 in 1965, rising with inflation to around £18,000 in 1980. Many have been improved internally whilst individual attentions to their frontages have added character to satisfy the artistic tastes of their owners.

The Quadrant, Wonjord Road

Doorway-38 WonfordRoad

Following (right) from Radford Road into Fairpark Road, and left into Dean Street, a right turn leads to Temple Road facing on to Bull Meadow, a public recreation park ofimmcnsc value to the surrounding densely —populated neighbourhood. Bull Meadow takes its name from the Bull Inn, which stood nearby in Magdalen Street up to the 17th century. It was designated a Recreation and Pleasure Ground in 1889 by the Exeter City Council under the Public Health Act of 1875. Its present formation was largely determined by the building of Magdalen Bridge in 1832, and considerable earth filling over the culvert cotirse of the Suthrook Stream which flowed through the arch at the right—lmnd end of the hridge. The retaining wall oithc bridge presents a magnificent example of masonry in Pocombe stone, with a coping of Dartmoor granite. Iron railings and gates once enclosing the Meadow were removed for use in World War II.

Bull Meadow from Magdalen Bridge

Pavilion Place

Leaving Bull Meadow by the steep path up to Bull Meadow Road, the Alice Vlieland Clinic lies on the left; built in 1929 as a Child Welfare Centre, it now serves as a health centre controlled by the Devon Health Authority. Behind the wall on the right is the Dissenters’ Burial Ground, now disused, and from the footpath in Magdalen Street can be seen thejews’ Burial Ground, still in use. Across the way is a footpath leading to the Friends’ Meeting House and its burial ground. These three distinctive burial grounds for non-conformists sited outside the city wall, are reminders of the strong religious differences which — even in death — were so strongly defined by our fore-fathers.

Next on the right towards South Gate comes Wynard’s Almshouses with their own Trinity Chapel. Built nfHeavitree stone in 1430 as William Wynard’s Hospital for twelve poor people, the buildings were restored in 1856 and adapted to their present use as a centre for social services in 1972. William Wynard was Recorder for Exeter, 1418 to 1442. The courtyard of his charitable gift retains the delightful medieval atmosphere it held when described as “newly built by the said William Wynard, a certain house called God’s house, without the South Gate of Exon.”

Across the road is the Vest of England Eye Infirmary; founded in Holloway Street in 1808, it moved to Magdalen Street in 1813, and into its present building in 1900. It is second only to Moorfields in seniority in England.

The West of England Eye Infirmary — detail of gable feature

Friends’ Meeting House, oJfMagdalen Street

Wynard's - the Courtyard

The only neighbour on the west side is the Acorn Inn. Isolated on an island, encircled by a surge of traffic Ibr most of its daily life, the Acorn is successor to a former inn which stood among the gabled buildings which sprang up in Magdalen Street after the Civil War.

Continue past the south side of the former Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital to a monumental plaque set in the wall denoting the original site of Palmer’s Almshouses endowed lbr four widows, who, by Palmer’s will of 1487, each received £1.1. 10 (l .09) annually until an increase was made in 1704!

Near South Gate, at thejunction of Southernhay with Magdalen Street, stood a terrace of residences with Georgian-style frontages which (when maintained in good order) added character and charm to one of the main approaches to the city. Allowed to fall into disrepair through many years of neglect, the buildings were demolished in 1976— to the dismay of the Civic Society, who campaigned for their survival. The site now awaits its resurgence if a ‘developer” can be found — may the outcome be a worthy contribution to the the street scene of Exeter.

Site of Palmer’s Almshouses, A’tagdalen Street

Acknowledgements

Listed Properties in the St Leonard’s District

The Exeter Civic Society is grateful for advice arid assistance given in the publication of this booklet. The writer’s task has been made enjoyable by the interested response to his requests lbr inlbrtnation. Particular thanks are due to the staffs of the Devon County Record Oflice and the West Country Studies Library for help in consulting parish records and for permission to reproduce photographic material; to the Rector oUSt Leonard’s, The Revd. Prebdy. George Bevingron, for access to documents relating to the history of the parish; to the President and Members of the Devon & Exeter Institution for permission to reproduce prints from the Library’s collection; toJohn Saunders, University Photographic Unit, and Michael Turner for photography; to Rodney Fry for drawing the walkabout map; to Michael Stocks for his pen-and-ink sketches; to Miss P V Pitman, whose drawing of the Quay is reproduced by permission of the Directors, Royal Albert Memorial Museum; Professor V G Hoskins has kindly allowed me to quote from his book: “Two Thousand Years in Exeter”. Finally, I have had the generous help of my wile in arranging and typing the production of an amateur.

Gilbert Venn

Published by Exeter Civic Society Hon Sec. Mrs S Penberthy 6 Hoopern Avenue Exeter

St Leonard’s has a great many buildings listed by the Department of the Environment as being of especial architectural and/or historical interest. It is regretted that space does not allow so many buildings to be recorded in this booklet, but a complete list in alphabetical street order can he seen at the City Council Planning Ollice.

Designed byjustin Beament FSIAD

Printed by Chevron Press Exeter

Print of Great Madford House, built by Sir George Smith about 1600